Kabin Maharjan

Almost all people speculated that the earthquake will hit Nepal soon and it did on 25 April, Saturday at 11:56 am. It was of 7.6 magnitude, making epicenter at Barpak, Gorkha. From then, there are 318 aftershocks, scaling 4 and more magnitudes till now according to National Seismological Center, Nepal.

Government statistics shows 8,844 dead; 22,307 injured; 5,98,401 governments and public building fully destroyed; 2,83,585 governments and public building partially destroyed till this date. Fourteen districts, especially west and central north-hills and mountain districts were among the highly affected districts. Nepal government estimated a loss between 5 to 10 billion dollar in this devastating earthquake. This quake has turned out to be a costlier after the quake of 16 January, 1934’s (Nabba Sal Ko Bhukampa), but has also taught us many things.

[quote_box_left] Author [/quote_box_left]

Author [/quote_box_left]

With this crisis comes a great dissatisfaction and frustration of affected people, not towards the natural phenomenon earthquake, but towards the slow response and relief initiation of the State. On the other hand, the State itself, aid organizations and personal level supporters are trying their best to respond, nevertheless, were facing many challenges in rescue, relief and supplying basic resource and services to the affected locations. There have been challenges in terms of coordination, mobilization, available technical resources etc. in the process.

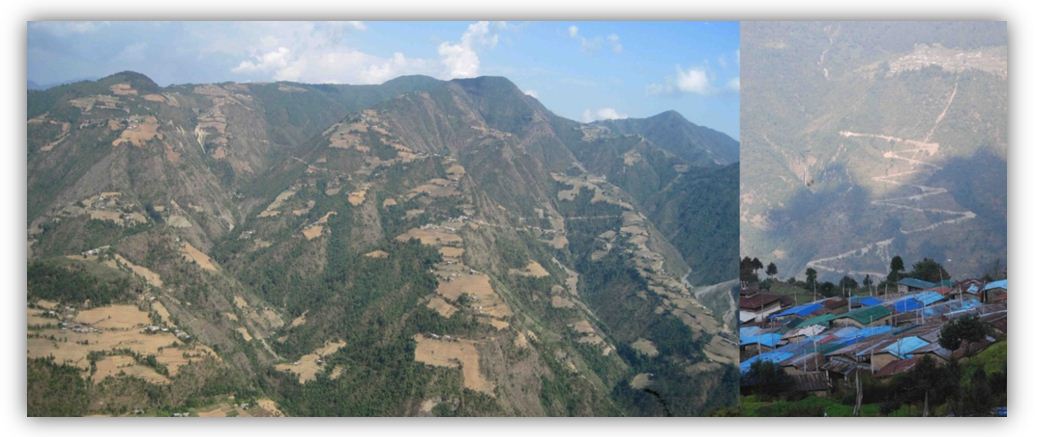

However, out of these many challenges, two challenges also stand out the most: Geography and Scattered settlements. No doubt that the geography of the affected areas has harsh terrain. Even the Logistics officers of United Nations World Food Program, engaged in earthquake relief, have admitted that the geography, mountainous terrain and poor roads are making difficult to respond. Various in-house study like Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), 2011 and Nepal Living Standards Survey (NLSS) 2010/11, have also indicated that access to basic infrastructure and facilities in rural areas is very poor. It is expected that on an average, rural households require over two hours and in mountains, requires as much as day to reach the nearest urban areas and market. With remoteness and harsh terrain, the challenge in rescue and relief is further amplify by the scattered settlement in the affected areas.

I get to experience closely, the challenges placed by these nature of settlements, as I also got engaged in the relief activities at Sindpalchowk and Dhading districts. For me and my friends, it would take two-three hours minimum, just to reach one settlement through motorbike and probably the same time to be back. Some road to the settlement needs four-wheeler vehicles. On whole day we hardly could reach out couple dozen household with relief materials. This is exactly what I would considered had happened with every aid distributors. Option for helicopters is also not always feasible as they need wide and safe open space to land and in addition the location should be near to the affected area. Hence, it is obvious that it will take a while before things gets distributed properly, in spite of their availability and willing efforts.

For a moment, let’s scale this scenario up to the rehabilitation stage to broader frame of rural development of Nepal from the perspective of settlements. Basically, human settlements are divided mainly into urban and rural settlements. In context to Nepal, the rural settlement can further be seen through the structure concept of linear settlement (A linear pattern of shelter along a road or river), cluster settlement (group of combined settlement together forming nucleus model with a trade or main route) and scattered settlement (spread out shelter with sub-trails). Based upon the compactness, the Tribhuvan University, Department of Geography, identify three settlement patterns: Agglomerated settlements (contains 5 or more houses together but not attached to each other); Compact settlements (contains many houses exceeding 5 and attached to each other) and Dispersed/isolated settlements (less than 5 houses at one place and some having distance between each homes). CBS survey of 2011 identifies around 83 percent of total population live in rural areas and it is also accompanied by huge number of scattered settlements that has limited facilities, infrastructure and opportunities. One study by Department of Urban Development & Building Construction (DUDBC), Nepal in 2003, estimates to have more than 30,000 such scattered settlements in country. Compared to Tarai and Mountainous region, Hilly region poses more scattered community.

Given the dispersed/isolated/scattered rural settlement patterns, the per capita costs for construction, operation and maintenance of basic infrastructure and facilities will be extremely high, if covered the whole scattered settlements. This is where the concept of Compact Rural Settlements (CRS) can be linked. It is the effort to concentrate the scattered settlements to compact core areas with systematic infrastructure, services and economic transitions.

Scattered and clustered settlements

The National Planning Commission of Nepal; United Nations Human Settlements Program (UN-Habitat); National Urban Policy 2007 and Land Use policy 2012, these are some institutions and documents that insist for the revision and scientific restructuring of the rural settlements in the form of CRS that could contribute in maintaining better access over basic infrastructure and facilities from the state and other sectors. This concept will also complement the ‘Residential Area’ under land zoning concept forwarded by Ministry of Land Reform and Management through Land Use Policy, 2012, to scientifically plan for the residence in certain areas. Supporters of CRS also claims that it not only maintains better access but also minimize environmental degradation and disaster risks. It could serve as a win-win approach as rural communities get better access to basic services and planned settlement. On the other hand, the state and non-state actors could provide an easy concentration of intervention with more efficient and effective socio-economic returns over development investments and resources. CRS could be the window of opportunity for the rural development in this crisis as we have to rebuild all the villages affected by quake including scattered settlements. If we dare, every crisis offers a window of opportunity and we have the rational reason to do it this time. Hence, CRS would be the key for rural development approaches and processes in Nepal.

This kind of resettlement or relocating people is not a new phenomenon. It has been carried out globally, whether it is to ease resource scarce geography, relocating due to development projects or resettlement of refugees. Nepal has also adopted mass resettlement program of hilly people to Tarai during 1960s, which had many reasons: to eradicate malaria, ease natural resource pressure, expand livelihood strategy and some geo-political reasons. However, relocating claim in this article does not mean mass migration to urban areas. It is just to restructure and discourage scattered settlement and bring the settlement into cluster within their nearest possible core settlements in rural areas itself, so that better public services could be viable and provided efficiently. Thus, this article also acknowledges the emotional attachment to the ancestral place and their customary values. Only the challenges in the process of resettlement or relocating would come under the land tenure issues, as which land to utilize and whose land for CRS? Whether it is on private land or public land? Should state compensate on private land if acquisition is made for CRS? Etc. This challenge could be address by implementing Land Use Policy, 2012. However, the challenge weights less compared to overcoming national earthquake crisis and rural development return that CRS offers.

Author is the researcher under Land and Migration issues and the visiting faculty at Kathmandu University, School of Arts.